From the Beginning of Ninth Century until 1767

During this period we can distinguish two chronological periods, the dividing line being the Ottoman Conquest. In the first, the Archbishopric of Ohrid was founded in the year 1018, after the collapse of Samuel’s Bulgarian state, and the Emperor Basil II issued three bulls (the Emperor’s decision on ecclesiastical issues) giving a total of 32 ecclesiastical provinces to it. A very large independent archiepiscopate was thus created, on which depended the eiscopates that are part of Albania today: Glavenica – Akrokeravnia, of Belegradit – Pulkeriopolit (Berat), of Çernika, Adrianopolit and of Butrinti. In the eleventh to the thirteenth centuries, the Metropolis of Durrës continued to depend on the Patriarchate of Constantinople. Among the hierarchs who directed it are known: Laurenti (1025), Constantine Kavasila (1180), and Romanoi (1240). The last Metropolitan of Durrës under Constantinople is mentioned in the year 1280, when it appears under the Archdiocese of Ohrid. It was Durrës that was the birthplace of the great twelfth-century Byzantine musician Saint John Kukuzeli (although by other accounts it is in the fourteenth-century). He lived on Mount Athos and Mount Athos was also the home of two other fourteenth-century ascetics from the region, Saint Niphon from Lukova of Himara, and Saint Nili Erihioti from Kanina.

After the dismemberment of the Byzantine Empire by the Latins in 1204, the New and Old Epirus region was influenced by the expansionist plans of the Anzhuinë Kings of Naples and the commercial plans of the Venetians. With the formation of the Despotate of Epirus (1267-1479), many of the episcopates located in the territory of modern Albania found themselves facing the impact of change, but this is impossible to discuss in this brief historical summary.

By the end of the eleventh century, the Roman Catholic Church enhanced its efforts to extend its influence further south (with the creation of the Episcopates of Kruja, Antibarit (Tivarit), Shkodra etc.). Particularly from thirteenth century on, after the Latin rule (1204 – 1474), the northern part of modern Albania was strongly influenced by Roman Catholicism.

In 1273, after the death of the Orthodox Metropolitan of Durrës, after an earthquake, a Roman Catholic bishop moved into town. The Serbian invasion in the fourteenth century caused devastation in many provinces. At the same time, some Albanian families (such as the Topia, Balsha, Shpata, and Muzakajt) formed small principalities. In 1335, the Byzantine Emperor New Andronicus undertook a military campaign from Constantinople via Thessalonica, and arriving in Durrës, imposed Byzantine domination on his revolting subjects. Later the powerful leaders of the local Topias family gave Durrës to the Venetians, who kept control of the city from 1392 until 1501. At the end of this first phase appears the heroic figure of George Kastriot Skanderbeg, who with his wars (1451-1468) will be the last symbol of Christian resistance against the Ottomans. Finally, Durrës fell into the hands of the Turks in 1501 and the Ottoman Conquest was complete. During the time of dependence of the Metropolitan of Durrës under the Archdiocese of Ohrid , the region of Durrës is mentioned once under the metropolitan title “of Durrës, Gora-Mokrës”, and sometimes stands as Metropolitan “of Durrës” and the Episcopate of “Gora-Mokrës”. The names known of the Metropolitans of Durrës for this period are: Daniel (1693), who later becomes Metropolitan of Korca (1694), Kozma (1694), “Metropolitan of Durrës and Dalmatians” Neofiti (1760), and Gregory (1767) .

Regarding the time of the establishment of the Metropolis of Belegradit (Beratit), we have no information. The Belegrad name appears at the beginning of the fourteenth century. This city, which was also called Berat, was conquered by the Ottomans at the time of Sultan Murad in 1431. Twenty names of the hierarchs are mentioned, of whom the best known are: Ignatius (1691-1693), who later becomes Archbishop of Ohrid, and Joasafi I (1752 to 1760 and from 1765 to 1801), during his rule the ecclesiastical province of Belegradit returned to the throne of Constantinople.

Even before the town itself was built, in 1490, the district of Korça was included in the Metropolis of Kostur (Kastorias), and this itself was under the jurisdiction of the Ohrid Archdiocese. The Metropolis of Korça was founded at the beginning of the seventeenth century, including under its self the Episcopates of Kolonja, Devolli and Selasfori (Svesdas). The first known Bishop of Korça is Neofiti (1624-1628). In 1670, the Archbishop of Ohrid, Parthenios, from Korca, elevated his mother town to a metropolitan seat, titled Metropolis of Korça, Selasforit and Moskopolit (Voskopoja).

The southern regions continued to be dependent on the Patriarchate of Constantinople. Of the 18 known bishops of Delvina, the earliest is Manasiu (1270), the foremost; Sophronius (1540), the well know intellectual; Zaharia (1670-1682), the compassionate and tireless preacher; Manasiu (1682-1695), the school builder in the villages of his province; in this aspect he was the precursor of St. Cosmas of Etolia. There is more evidence for the Episcopate of Drinopuli (eleventh – eighteenth century). Of the 41 names of its bishops can be distinguished: Sofiani (1672-1700), a heroic fighter against return to Islam; Mitrofani (1752-1760), an educated and eminent musicologist; and Dositheu (1760-1799), who oversaw the construction of about 70 churches.

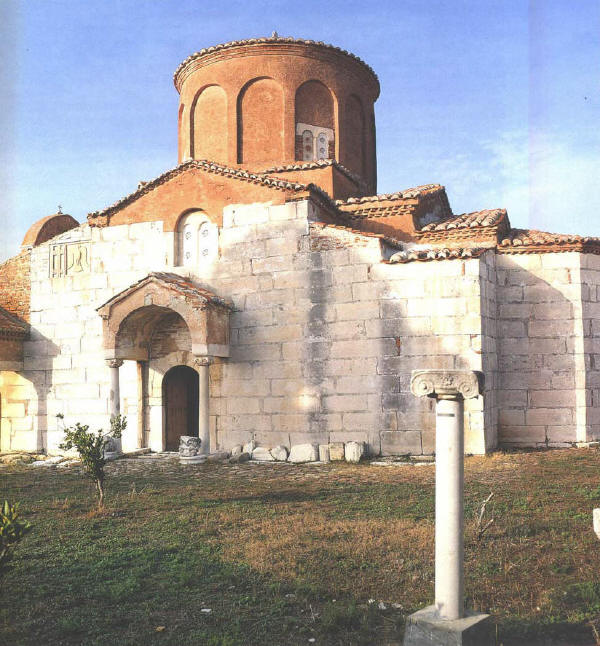

Under Ottoman rule the Church’s most serious problem was the continual massive conversions to Islam. It was the Albanian population that was most vulnerable to Islam: other reasons being there was a lack of Christian literature in the native Albanian tongue. At the same time, various Roman Catholic propaganda missions were active in the coastal region of Himara. To support the Orthodox, from seventeenth century on, new monasteries were built in many regions, which were even developed into centers of Orthodox resistance, of spiritual cultivation, of educational and social benefit, for example: the monasteries of Ravenina, Pepelit, Drianit, Çeoit, Poliçan, Çatistës, Kamenës, Leshnicës, Kakomisë, Palasa, Himara Dhermi Qeparoit, Hormovës, Hill, Ardenicë (Ardevusës), Apollonia, Joan Prodhromit (Forerunner) in Voskopoje, etc..

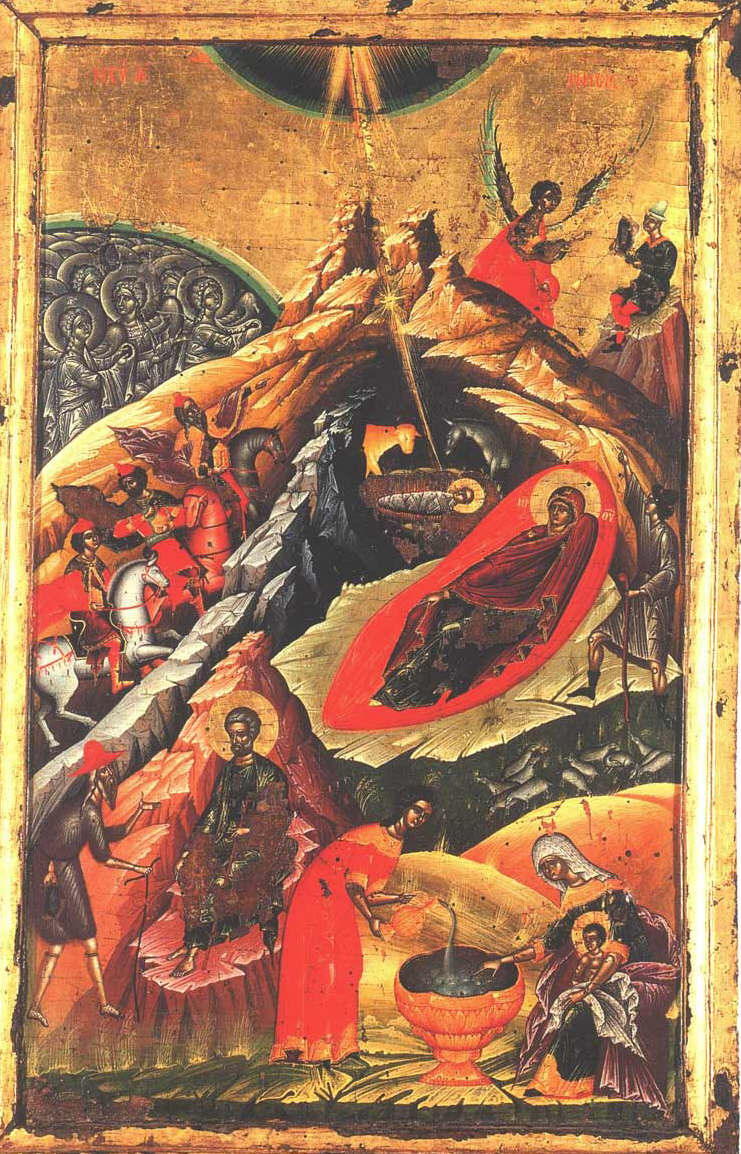

In many parts of southern Albania the resistance was strengthened by building churches and organizing schools. One of the most important centers of Orthodoxy was Voskopoja, built on an inaccessible plateau; it was difficult to go there. In the eighteenth century it had about 60,000 inhabitants, and enjoyed an astonishing flowering of economic and intellectual life. The New Academy (1744), with its library and printing press, was widely renowned. The town was bedecked with 20 churches. Until 1760 Voskopoja depended directly on the Archbishop of Ohrid, and then it became part of the Metropolis of Korça. Its fall began after the robbery in 1771, because it was part of the revolt of Orlofit, culminating in 1916, when it was burned by bands of unruly Albanian units.

To avoid forced Islamization and at the same time to maintain the identity of their origin, groups of captives in many parts of the Ottoman Empire chose to become “kriptokrishterë” [hidden Christians-kryptochristianoi]. In their public life they appeared with Muslim names and behaved as such, but in their family life they kept their Orthodox traditions. The most typical example of “hidden Christians” in Albania were the Tosks of Shpati, a mountainous area located south of Elbasan.

This phenomenon lasted from the end of the seventeenth century to the end of nineteenth century. There was no absence in this region of new martyrs: the hermit-martyr Nikodemi (Nicodemus) in 1722 (noted to be from Elbasan, but was from Vithkuqi and was martyred in Berat) and Kristo (Christo) Kopshtari or Arvanites, from the area around the river Shkumbin, martyred in Constantinople in 1748.