As regards art, the most helpful division seems to be one into periods of culture. The first is that of the Early Christian monuments, from the fourth to the eighth century. The second is the Byzantine period, from the mid-eighth century to the fifteenth century. The third covers the post-Byzantine period and the Turkish occupation (1501-1912).

Architecture

Early Christian

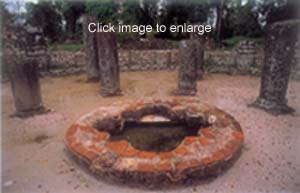

The monuments which excavations in the last few decades have brought to light date mostly to the fifth or sixth century. A basilica discovered at Tepe, outside Elbasan, is probably fourth-century. The commonest types of church architecture of this period are three-aisled basilicas. The side-walls are marked off by pillars (Arapaj near Durrachion, Byllis, Amantia) or by piers (Elbasan, Bouthrotos), or by pillars and piers alternating (Hagioi Saranta): some of them have a triple conch (Lin, Balsh). Hall churches have been found at Antigoneia, Apollonia, Durrachion, and Ha¬gioi Saranta. Round, square or octagon Early Christian baptisteries still survive, at Phoinike, for example, Lin, and -the finest of all- at Bouthrotos.

Byzantine

New typological forms can be seen in the tenth-century churches. Sometimes these are single-aisled (Prophetes Elias, Buali near Premeti), sometimes they follow the basilica tradition (of Hagios Stephanos, Drymades, etc.). Extant from the early post-Byzantine period is the odd-looking basilica of Hagios Nikolaos at Perchonti. The main innovation is a new type of domed cross-in-square church (Ano

|

Baptismal font in Bouthrotos. |

Episkope, Kosina). Much attention is paid to the exterior of the church as well (dome, decorated windows, combination of brickwork and stonework). A typical example is the church of the Panagia at Ano Lambovo, of the tenth century (or the thirteenth, according to others), which is of exceptional artistic merit. There is an architectural renaissance in the thirteenth and fourteenth century. In the Skodra region one can see the influence of Western European architecture in thirteenth-century churches, such as Hagioi Sergios and Bakchos on the banks of the river Buna, or the church at Vau i Dejes. There are often Byzantine and Romanesque features side by side. Byzantine churches show Romanesque influence, while the Byzantine paintings are still dominant even in buildings in the Romanesque style. In the south singled-aisled churches continue to be built (for instance Hagios bannes at Bobostitsa), basilicas become rarer, and the domed cross-in-square type is the rule (e.g. at Marmiro, Aulon (Vlorë), the Monastery of the Theotokos, and Zvernec).

The Panagia Blacherna (restored in the sixteenth century) and the church of Hagia Triada at Berat are a plain variant of the straight type, whereas the church in the Monastery of theTheotokos at Apollonia is built in a complex variation. A Byzantine monument superb for its (perhaps thirteenth-century) architectural and decorative composition is the church of Hagios Nikolaos at Mesopotamo.

Post-Byzantine

Church building came to a complete standstill in the first phase of the Ottoman occupation. The sixteenth century saw new towns spring up in mountainous regions alongside the old towns. Examples were Moschopolis, Vithykouki, and Nica, where churches were built that stood out by the simplicity of their architecture and their spareness of form. From the mid-sixteenth century onwards, well-developed architectural forms made their appearance in the monasteries, which were usually built in out-of-the-way places. Two typical sixteenth-century buildings are the church of the Soter (1540-1560), at Remist near Premeti, and the church of Hagios Athanasios (1513) at Mazhar near Politsiani. Two distinctive seventeenth-century buildings are the church at Barmash (Kolonia), and the katholikon of the Monastery of Hagios bannes Prodromos (1632).

In the eighteenth century more churches were put up, with improved architecture and decoration. The main emphasis was on the interior space, the exterior of the building remaining plain. It was a century of substantial economic and social progress, with the position of the Albanian feudal lords becoming stronger and relative political calm. At the same time, however, there was an increase in Islamization, and there were laws that strictly forbade the erection of Christian churches. For this reason, both in towns and villages, churches were built so as to be indistinguishable from dwelling-houses. A good example of a post-Byzantine church is the cathedral church of the Theotokos (1797), at Berat. A commanding building in the Mouzakia district is the Ardeuousa (or Ardenitsa) Monastery: what we see today was built on the ruins of a Byzantine monastery. From the middle of the eighteenth to the middle of the nineteenth century, churches were built in practically every village of the Mouzakia, the representative type being the three-aisled basilica with wooden pillars and a flat roof, as for example at the church of Hagios Georgios (1776) in Libofsha. The five surviving churches at Moschopolis have wonderfully shapely architecture.

Mosaics

Linked with the architectural monuments, there survive noteworthy mosaics (at Tirana, Arapaj near Durrës, Hagioi Saranta, Antigoneia and elsewhere). Their subjects are not from religious art: they follow the secular tradition in their schematic meanders, depictions of plants, birds, animals, and rural scenes. The most important of these mosaics, the mosaic floor from the basilica at Mesaplik is now accommodated in the Tirana Museum. It shows the portrait of a male in profile, with the inscription APARKEAS. Some of the mosaics look rather ungainly, but nevertheless they have great artistic value, and the same can be said of the mosaic in the round baptistery at Bouthrotos. The only extant wall mosaics are to be found in the chapel of the amphitheatre at Dyrrachion. Here the figures depicted are Saint Stephen; an empress, or perhaps this is the Virgin Mary; archangels; and donors. These mosaics show strong similarities to those at Thessalonike.

Miniature art

The earliest examples of painting are the miniatures in the famous Berat purple codex. An extreme rarity, this is a manuscript Gospel, probably sixth-century, written in capital letters. Most other manuscript miniatures date from the ninth to the fourteenth century, and they are remarkable for the beauty of their gilt lettering. Examples of Byzantine craftsmanship at its finest are to be found in two late eleventh – or early twelfth-century codices from Aulon. Here the figures recall comparable tenth-century works from Constantinople.